As a young teenager, Andrew Zimmern came home from summer camp to learn that an accident during surgery left his mother permanently disabled. When he walked home from the hospital with his father, he looked to him for emotional support. But, instead of acknowledging their grief, his father masked his pain and encouraged his son to do the same.

Before his mother’s accident, Andrew admits he had a fortunate childhood, including private schools, multiple homes and trips around the world. But there was a layer of brittle insecurity underneath the shiny exterior. “There was never talk about real feelings or real events in people’s lives,” Zimmern explains. “My dad had lived a closeted life as a young man, so that carried shame was already inside me.”

With his mother hospitalized, and his father growing more emotionally unavailable, Andrew only became more isolated. Without the ability to talk about his feelings, his pain grew into resentment, anger, and, eventually, substance abuse. “Coping with life absent drugs and alcohol became impossible for me once I learned that drugs and alcohol existed,” he says.

By the age of 14, he was drinking, smoking marijuana, and taking pills every day. These habits followed him into adulthood and impacted his career. Even while running restaurants in New York City, Zimmern was controlled by drugs and alcohol. He began stealing from friends and family and doing anything he could for money to fuel his addictions.

Eventually, his addictions cost him his job, and he became homeless. In January 1992, he bought a case of alcohol and a handful of pills and attempted to take his own life. “When I woke up no less than 48 hours later, I wasn’t dead,” he says.

This realization led to a moment that he never thought would come. After decades of drug abuse and emotional isolation, Zimmern called a friend and asked for help. He had carried his family’s shame for decades, and finally, for one brief moment, he found the strength to share his pain and rely on another person.

“I did nothing to deserve that pause in the shame cycle of my life,” he explains. “Yet, it happened.”

After asking for help, recovery wasn’t easy – but it was achievable. With the encouragement of his friends, he found a rehab center and enrolled in a 12-step program.

For the first time in his life, he faced his thoughts instead of numbing them – and he shifted his focus from taking to giving. His perspective cleared, his goals changed, and soon after, his career took off. He went from cooking in restaurants to hosting his own television and radio shows.

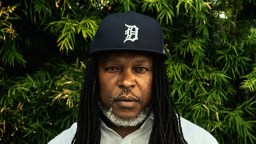

Now, decades later, 63-year-old Zimmern is a celebrated celebrity chef, author, and television personality, and has earned an Emmy and four James Beard awards. Still, he remains grateful for that single moment of vulnerability that changed everything – when he asked for help and was met with love, dignity, and respect. And he discovered that redemption was waiting for him all along.

We interviewed Andrew Zimmern for Perception Box Stories Untangled, a Big Think interview series created in partnership with Unlikely Collaborators. As a creative non-profit organization, they’re on a mission to help people challenge their perceptions and expand their thinking. Often that growth can start with just a single unlikely question that makes you rethink your convictions and adjust your vantage point. Watch Zimmern’s full interview above, and visit Perception Box to see more in this series.

ANDREW ZIMMERN: I used to be a user of people and a taker of things. I used to be as self-absorbed as anyone that I've ever known. Fourteen years of evolving from a pretty nice kid into an irredeemable person.

In 1974, my mother had some minor plastic surgery because the bikini lines dropped, and she had an old appendix scar. They cut off the oxygen supply to her brain during the anesthesia process, and she woke up a vegetable. She lived into her 80s, but she was never the same. Her physical looks changed. Her intelligence, her mental capacities, her emotional capacities—all changed.

So when I came home from summer camp to find that, and my father gave me the talk on the walk from the hospital back to our apartment, telling me that this was the one time we would talk about this and we would never mention it again, instinctively, I knew that's how we dealt with things in our house. The problem was I was in horrific pain. I had just lost my mother, and I just became an anger and resentment machine. That early perception of myself and then the actions that resulted were essentially what almost killed me.

My alcoholism, my addictions, are a direct result of both nature and nurture. Coping with life, absent drugs and alcohol, became impossible for me once I knew that drugs and alcohol existed. Growing up in the 60s in New York City, I had a very, very lucky childhood: private schools, everyone had a second home. I'd been around the world two or three times by the time I was 13 years old. I had a loving and creative mother. People ask me when I knew I was going to get into food, and the answer is—I’ve never not known.

My father would lower me between these boulders the size of houses on Georgica Beach in East Hampton to pull up big ropes of mussels that we would clean and steam over a pot for dinner. We crabbed, we went eeling, we went clamming. I never knew a lifestyle that didn't place a high priority on food, on travel, on adventure. Our household was a wonderful place to grow up in many ways, but in many ways, it had a lot of deficits. I was the recipient of so much carried shame. There was never talk about real feelings or real events in people's lives. In fact, quite the opposite.

My dad had lived a closeted life as a young man. So that carried shame was already inside me. I was obsessed with not getting what I thought I needed, not having what I wanted, and that you were always getting the stuff that I deserved. I didn't want to feel the feelings that I was feeling. And I also knew I couldn't talk about them. By the time I was 14, I was a daily pot smoker, daily drinker, daily pill user. It became my higher power.

There is not a moral line that I had in the sand that I didn't cross as an addict and alcoholic. I would be running some of the best restaurants in New York—pretty successfully—snorting speedballs, doing three, four, five days in a row, and then when I'd have my two or three days off, that's when I had this other life. I would have brief moments of clarity once a week where I would just be like, “Holy fuck, I just stole from my grandmother's medicine cabinet. I just broke into a friend's home. I just rolled someone outside of a nightclub.”

At one point, when I physically wasn't able to steal anymore, I actually had a guy in a nightclub who wanted to pay me money to jerk him off in the alley, and I said, “Sure.” Because I wanted the money. Every decision was being dictated by the need to get high. Absolutely everything. It's when I couldn't hold down a job at all, I became homeless and was living on the streets. That's when things got a lot worse. The more you continue to use, the more consequences you have. And that creates a greater cycle of shame and anxiety and magnifies your own traumas.

All I wanted to do was die. And so, in January of 1992, I stole a bunch of jewelry from my godmother, hocked it, walked across the street to the liquor store, bought a case of vodka, bought a handful of barbiturates, and tried to kill myself. When I woke up, no less than 48 hours later, I wasn't dead. I called one of my friends and I said the words that I had never used before in my life, which was, “Can you help me?”

That turning point in my life is probably the most profound hinge event I've experienced in six-plus decades of walking around planet Earth. I did nothing—nothing—to deserve that pause in the shame cycle of my life that allowed me the 30 seconds of clarity to actually know what to say, let alone say the words, “Can you help me?” But yet, it happened. I knew somehow, on some level, that if I didn't get sober then, that I was done for.

After sleeping at Clark's on his couch for a couple nights, I wound up walking into what I thought was a cup of coffee with my friend Pamela, and I walked into what was an intervention. And I just said, “What time’s my plane?” I got involved in a 12-step program in as deep a way as I've ever gotten involved with anything in my whole life. It turns out that my lifestyle before sobering up dulled a lot of my abilities. So I found success pretty instantaneously. I left day-to-day restaurant operations and got into TV, writing, radio.

I think oftentimes people want to know, “What was it like? What made you make this decision?” I don't try to seek the answer to a lot of these questions. I simply accept them as being true. I had a transformative experience that cannot be explained by my own behavior or my own thinking. I'm learning things now at age 63 that I think a lot of people learn in their 20s. I don't ask what I can take from a situation; I ask what I can give to it. The perspective shift for me—away from putting me first—really began after I realized that asking for help was a sign of strength, not a weakness.

That's what happens when you sprinkle a human being who’s irredeemable with love and dignity and respect. If we give them enough of that, human beings can recover from anything. And I am living proof of it.