How glorifying ignorance leads to science illiteracy

- Many of us, when we’re young, feel the pressure to not appear too smart, knowledgeable, or curious, as it leads to social ostracism and being labeled as uncool.

- As we move into adulthood, many of those same pressures find us, and we’re quick to repress those same qualities in order to better fit in with those around us.

- But it’s those very traits that lead to not only science illiteracy, but the glorification of ignorant, factually untrue positions. Expert-level knowledge is mandatory for a healthy society, and there’s no substitute.

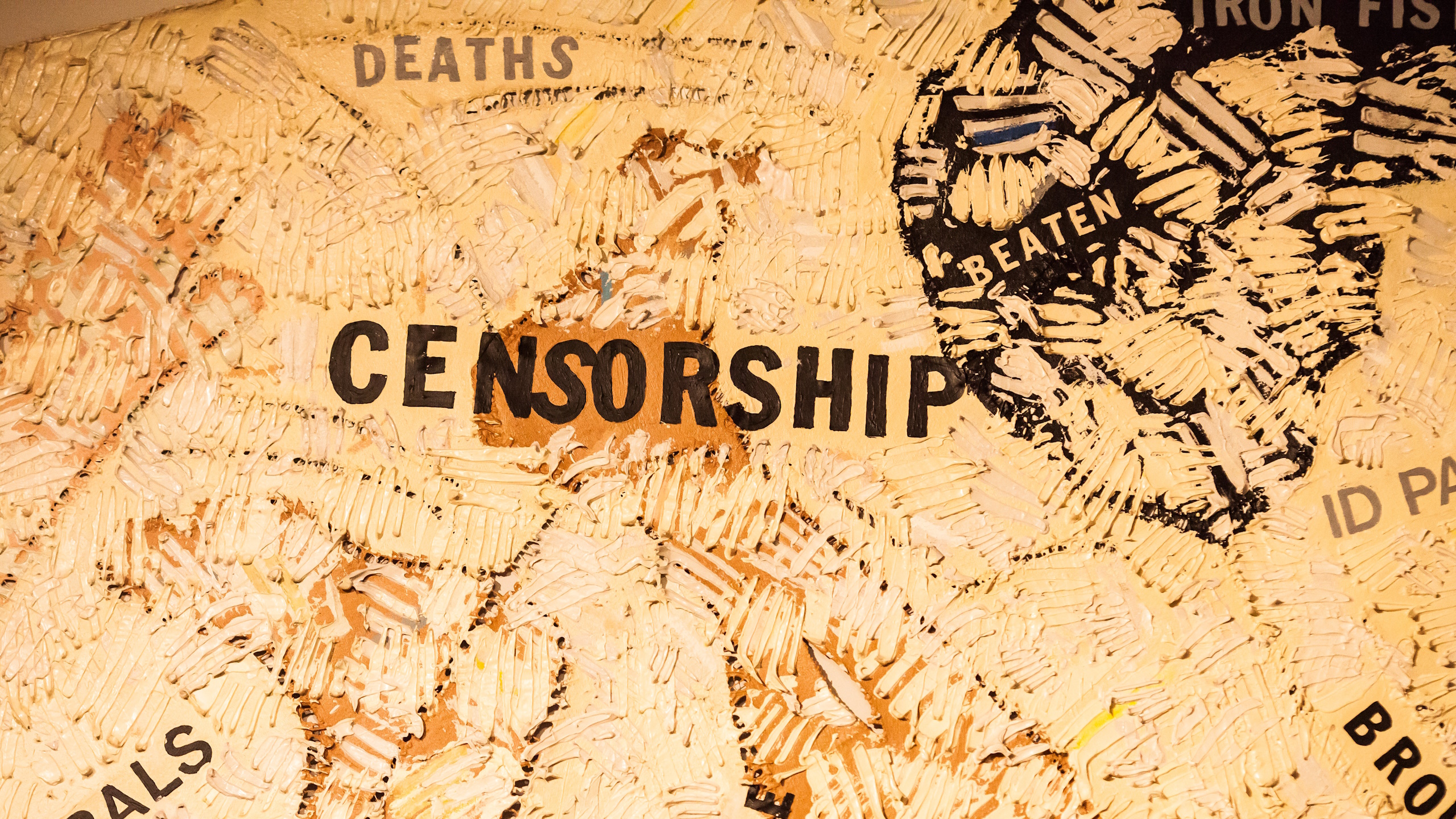

All across the country, you can see how the seeds of it develop from a very young age. When children raise their hands in class because they know the answer, their classmates hurl the familiar insults of “nerd,” “geek,” “dork,” or “know-it-all” at them. The highest-achieving students — the gifted kids, the ones who get straight As, or the ones placed into advanced classes — are often ostracized, bullied, beaten up, or worse. It’s a version of the social effect known as tall poppy syndrome: where if someone dares to stand out, intellectually in this case, the response of the masses is to attempt to cut them down.

The social lessons we learn early on are very simple: if you want to be part of the cool crowd, you can’t appear too exceptional. You can’t be:

- too knowledgeable,

- too academically successful,

- too advanced compared to your peers,

- or too smart.

Someone who knows more, is more successful, or who seems to be smarter than you is often seen as a threat, and so in order to prevent them from standing out too much (or surpassing too many others), we glorify ignorance as the de facto normal position.

But ignorance isn’t normal at all; it’s an incredibly dangerous place for anyone to be. Choosing to remain ignorant harms your development as a child, but leads to science illiteracy, which harms the entire world.

There are so many remarkable things that we — as a species — have figured out about existence.

- We know what life is: how to identify it, how it evolves, what the mechanisms and molecules are that underpin it, and how it came to survive and flourish here on Earth.

- We know what reality is made of on a fundamental level, from the smallest subatomic particles to the nature of space and time that encompasses the entire Universe.

- We know how matter behaves under extreme conditions, from the vacuum of space to the centers of stars to the ultra-cold conditions we can only achieve in laboratories here on Earth.

- And we know how our Universe evolved to become the way it is today, from the earliest stages of the hot Big Bang (and even earlier than that) to the formation of atoms, stars, galaxies, and the modern cosmic web.

Our most valuable explorations of the world and Universe around us have been scientific ones: where we learn about reality by asking it the right questions about itself, and by listening to the answers that are revealed to us through experiment, observation, and careful measurement.

Of course, not everyone knows all (or even most) of the answers to these big questions: not me, not you, and not even the best artificial intelligence programs. It’s impossible, in this day and age, for any single individual or entity to be an expert in all possible things. Most of us learn this at an early age: that most of what is known to humanity is not known to us as individuals, and that there are really only two paths available to us if we need some piece of information that we don’t currently possess.

- We can study to gain that relevant expertise, taking all the painstaking steps needed to learn it and become competent within that field.

- Or, we can go find someone with the appropriate, relevant expertise to learn what the answers to our inquiries are from them directly.

At least, that’s how you would behave if you’re genuinely interested in learning the actual answer, rather than relying on opinion, hunch, or the often-unwise “wisdom of crowds” (or an often-unreliable AI, for that matter). You’ll either undertake the research yourself to reach expert-level competence, where you’ll learn how to perform critical tests and experiments that determine the answer, or you can learn to discern whose expertise is worth listening to and why, and then to take that expert advice. That’s how you gain meaningful knowledge.

But many of us don’t choose either of those routes, and there are a number of reasons why people make alternative choices. First off, it requires making a series of admissions to ourselves that are very difficult to accept. These include:

- admitting that we don’t know everything,

- admitting that we might be wrong about something that we’ve thought or even publicly espoused,

- admitting that we might have been swindled by or placed our confidence in someone who’s a mere charlatan,

- the fact that changing our mind about something requires us to do additional research, work, and mental labor,

- and it requires that we recognize that our chosen heroes — which frequently includes the people we admire most — are often flawed, incorrect, or are knowingly telling a lie to further their own personal gains.

This is not an easy situation to be in, regardless of your education or background. It’s human nature to want to save face and appear like we knew the right answer all along. But, if we’re being honest with ourselves, that isn’t a real solution to problems that are rooted in our own ignorance, which (like it or not) is often substantial.

If you’ve ever pointed out a teacher’s mistake to them in school, you’ve likely gotten one of three types of responses.

- Perhaps the teacher considered what you said, admitted their mistake, and praised you for catching it.

- Perhaps the teacher recognized you were right and they were wrong, but wanted to save face, and so responded by ignoring your point or pretending that they didn’t make a mistake, such as by saying, “I was just testing you.”

- Or, worst of all, perhaps the teacher dug in deeper to their demonstrably incorrect position, insisting that they were right despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

We all hated the latter two responses as kids. Even as a child, you know when the adults are lying to you, to themselves, and to everyone else in the room. As Mike Brock just wrote recently, it’s the “capacity to think clearly about reality itself” that must be our most unbreakable trait as individuals, particularly when there’s pressure — peer pressure, social pressure, political pressure, etc. — to surrender that capacity over to whatever some arbitrary authority figure says.

What we knew was wrong back then, to deny the plain truths of reality, is still wrong today. Only now, as adults instead of schoolchildren, the consequences of embracing a demonstrably untrue reality are dire.

Think about all the small ways that we deny the reality of a situation on a routine basis, and what sort of downstream consequences it has for our lives, our health, and our well-being.

- When we deceive ourselves about the severity of an injury, the injury typically gets worse.

- When we deceive ourselves about an illness that we have, and fail to treat that illness appropriately, we significantly increase our risk of debilitating long-term consequences or even of death.

- When we deceive ourselves about our financial realities, we run the risk of spending beyond our means, and then not being able to pay for our essential needs later on.

Whenever we are dishonest with ourselves about the reality of the situation we find ourselves in, our comfort is often short-lived, as it’s usually followed by dire, inevitable consequences.

Sometimes, however, the consequences are either minor, invisible to us, longer-term than we’re willing to consider, or they affect someone other than ourselves. When your country doesn’t produce enough food, you might think about cutting down more trees to increase your farmland. But trees are essential for water management; without enough, your farmland might become a muddy wasteland, leading to a catastrophic famine. This recently occurred in North Korea, causing their great famine in the 1990s, and also in Brazil, where rainforest destruction to make way for soybean and cattle farms is reducing agricultural yields to their lowest productivity levels ever.

Despite whatever your initial intuition might have been about an issue, you must always — every time you acquire new, valid information — re-evaluate your expectations in light of the new evidence. This is only a possibility if you can admit, to yourself, “I may have been wrong, and learning this new information is essential in getting it right in the end.”

Every time we insist we already know everything, we lose an opportunity to learn and improve. When we insist that we’re perfect and infallible, we entrench ourselves in a position that runs the risk of being overturned when more and better information comes in. When the expert we once trusted turns out to be a huckster, fraud, or (worse) an ideologue, we have only two options open to us:

- we can either admit that we were tricked, duped, and must try to make amends and take a more correct course of action as a result,

- or continue farther down a road we know is rotten to the core, all while defending a position we know is indefensible on its merits.

There’s a reason why admitting, “I was wrong” is so difficult for so many of us, and why it is rarely an innate talent for humans to have, rather than a skill we must acquire. All of the solutions that require learning, incorporating new information, changing our minds, or re-evaluating our prior positions in the face of new evidence have something in common: they take effort. They require us to admit our own limitations; they require humility. And they require a willingness to abandon our preconceptions when the evidence demands that we do. If we don’t rise to those challenges, we’ll wind up living the life of a contrarian, engaging in actions that actively harm society.

Imagine a world where we followed the advice of the 1960s-era auto industry, who proclaimed that seat belts wouldn’t save lives, and so we never even bothered to install them in cars.

Imagine a world where we never accepted the germ theory of disease, and therefore never incorporated appropriate sanitation or antisepsis practices into society.

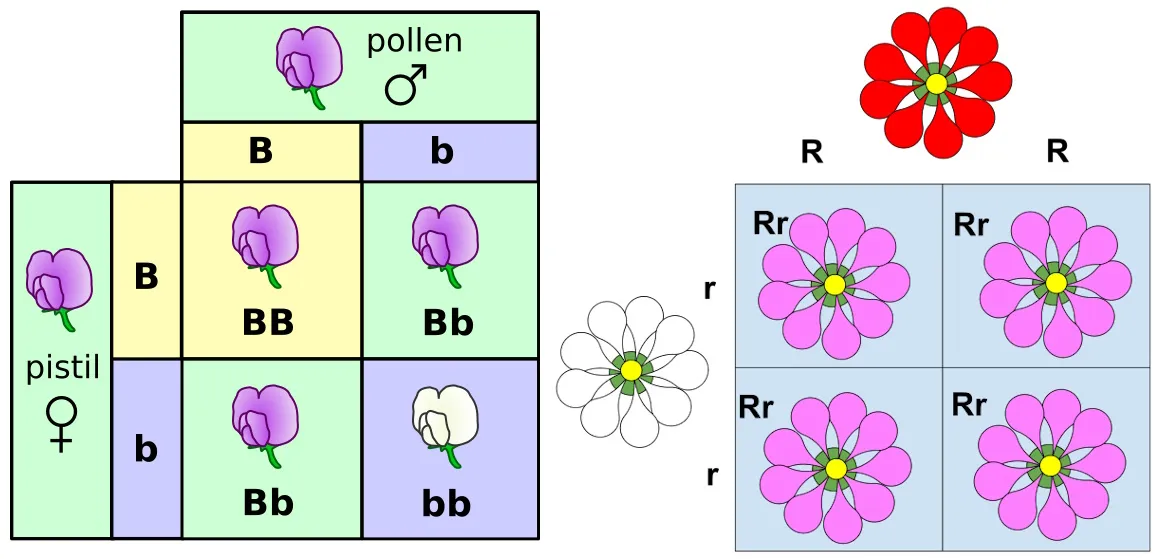

Imagine a world where, like the USSR from the 1920s-1950s, we rejected Darwinian evolutionary theory and Mendelian genetics, instead relying on fraudulent, incorrect science about crop yields, leading to unquantified famine and starvation.

Although these examples might be non-controversial in our society today, it’s only because public opinion on these matters — what we frequently call “common knowledge” — aligns very well with the scientific consensus on these issues. Frequently, public opinion and our proverbial common sense are terrible guides, and we are taken in by schemes, scams, and conspiracies that play on our fears. We’ve seen this occur recently, with large swaths of the general public rejecting the science about vaccination, water fluoridation, and many other medical, public health, and public safety measures. These pitfalls are not unique to laypersons; scientists and others with expert-level knowledge frequently fall into these traps, too.

Some of the ways this manifests in society might seem like low-stakes affairs that aren’t worth much effort. Maybe you laugh when you hear about a rapper claiming the Earth is flat. Or a basketball player saying we never landed on the Moon. Or at the 25% of the population who thinks the Sun orbits the Earth. But it’s not laughable; it’s something we should collectively be ashamed of. It’s a sign of how we’re failing as a society: where individuals are putting their personal phobias and (largely ignorant) ideological preferences ahead of the public good.

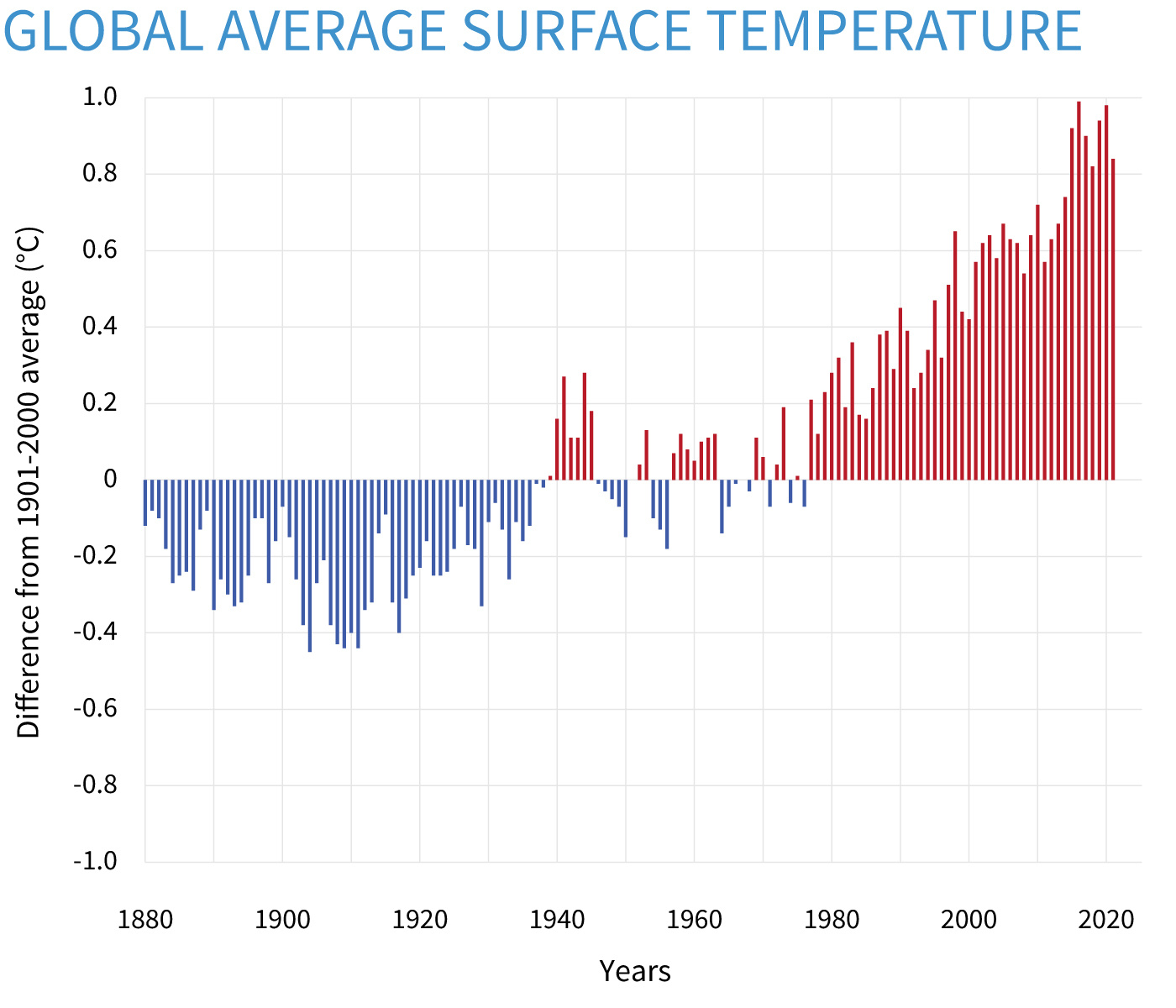

When we trust our own non-expertise over the genuine expertise of bona fide experts, terrible things happen. We wind up with cities without fluoridated drinking water, increasing cavities by 40% in the most low-income populations. We get vaccine-preventable diseases causing outbreaks and epidemics, including among populations of children who are either too young or too ill to protect themselves, individually, with a vaccine. We continue to pollute the Earth with greenhouse gases even as we’re experiencing evermore severe consequences due to global climate change.

In short, we act irresponsibly whenever we trust our own skewed assessments over the superior, expert-quality information that humanity has worked so hard, over centuries, to obtain.

Think about your reaction to the following sentence:

“You are not right about everything.”

Did you bristle? Did you respond angrily? Did you want to contest that statement, and perhaps argue that you’ve only ever been mistaken about inconsequential things, but never about anything that matters? You aren’t alone, if so. However, the fact remains that many of the opinions that you hold — and some of the facts that you believe to be true — will turn out to be falsely-held beliefs. Some of them, most likely, have already had their falsehood demonstrated beyond a reasonable scientific doubt. Unless you yourself are a huckster, trying to profit off of the willful deception of others, you must be open to changing your mind and deferring to the genuine experts who know more than you; otherwise, functionally, you serve as merely a mark.

Glorified underachieving, proclaiming falsehoods as truths, and the derision of actual knowledge are banes on our society. The world is made objectively worse by every anti-science element present within it. Nobody likes to hear that sometimes, they are (and are exacerbating) the problem itself, but if you’re someone who proudly proclaims your ill-founded positions publicly, that’s precisely what you’re contributing to.

In the end, it really is on each one of us to do better. The next time you find yourself on the opposite side of an issue from the consensus of experts in a particular field, remember to be humble. Remember to listen and be open to learning. The future of our civilization may hang in the balance.

This article was first published in May of 2019. It was updated in 2025.